Get Next Shodhyatra Update:

Phone:

079-27913293, 27912792

Email:

info@sristi.org

A JOURNEY FOR EXPLORING LOCAL CREATIVITY

Popular science movements in India and elsewhere in the world have often tried to take science to the people. It has been assumed that science is something outside our day to day life experience and its presence needs to be demonstrated through externally designed strategies, models and experiments. Creation of scientific temper, so defined, thus became a major goal of modernising societies.

The Honey Bee network disagrees with this perspective. We do recognise a need for increasing general awareness about the science underlying day to day life experiences. But we do not believe that this has to be seen as an injection of any fundamentally new value. For instance, cultivation of land, rearing of animals and management of other natural resources have always been based on scientific principles. Farmers did not just sow any crop at any time. It is possible that they did not know the scientific theories underlying many of the farming operations. But they knew the relationship between temperature, humidity, moisture and seed germination. At the same time, because of the excessive influence of the so called extension system built around modern chemical intensive agriculture, farmers’ ability to experiment, innovate and generate creative solutions to local problems did get impaired over the years. Some farmers, however, did not give up their exploratory spirit and creative urge to develop local solutions unaided by markets, NGOs, or state.

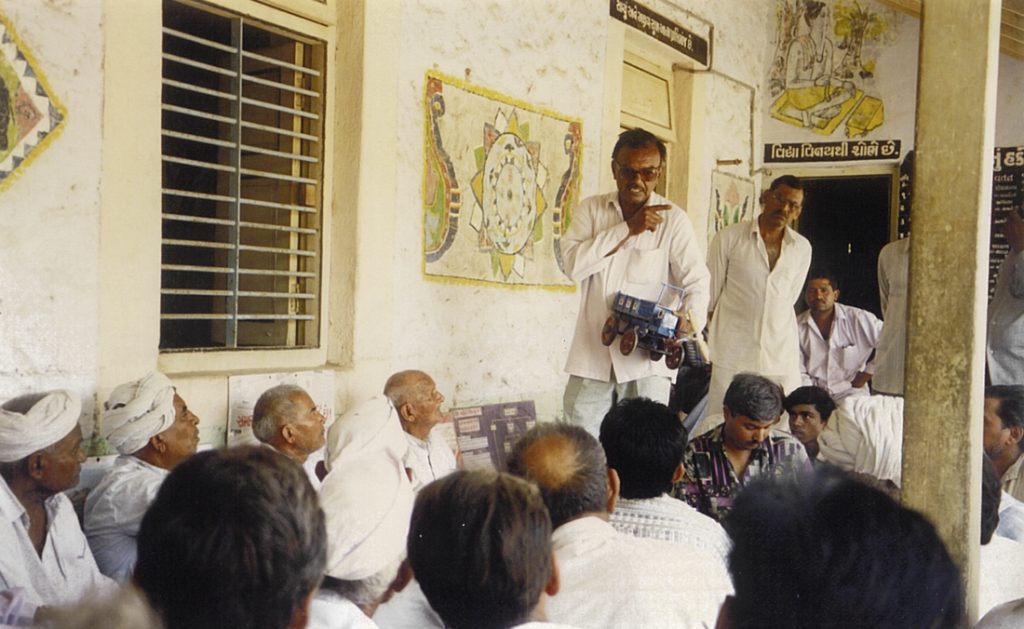

It is to seek such farmer men and women, honour local experts and innovators, generate consciousness about sustainable agriculture and conservation of biodiversity and share the experience of other innovative farmers that we embarked upon a Shodh Yatra (a journey of exploration). This journey of about 250 km was undertaken by foot on 15th May 1998 till 23rd May 1998 in Saurashtra, a dry region of western Gujarat, during the hottest part of the summer and was indeed very strenuous. There were days when we walked about 40 km, stopping in different villages, organising meetings, sharing innovations, showing computerised multimedia and other electronic databases in Gujarati on innovations. The rewards of this exercise were many.

The fact that we chose the most difficult time to walk when even drinking water was not available at times for 10 km at a stretch, served one clear purpose. That was the development of an instant rapport with the people whom we met. It also helped us experience a little bit of the suffering that people experience every day. We started the walk from Ramlechi village near Gir forest in a group of fifteen people. The size of the group varied during the journey. Some innovators joined us for a few days while others were with us throughout the journey. They brought with them their innovative implements like a tilting cart, modified water pulley and 10 HP tractor. We carried with us posters on various aspects of innovations besides models of implements and audio visual support for reinforcing the spirit of local experimentation. The idea was to convey that there are people who think differently and generate solutions but somehow have not become points of reference in our day to day life. Our concern was how to overcome the inertia and apathy towards the ethic of experimentation and generate respect for local knowledge that is in tune with nature. We honoured the most knowledgeable man or woman in every village and presented them with literature produced by SRISTI in Gujarati on innovations.

There were many moments of fun, fear and discovery all through the walk. During the first night halt in Hirenwel village on the outskirts of Gir Lion Sanctuary, we discovered three innovative farmers after a lot of persistence. One of them had developed a simple lock device to take out a damaged submersible motor from the bore. Another had developed herbal pesticides and the third came to rescue of a contractor building a structure in the forest. The technical supervisor was not able to align the structure properly. An illiterate labourer came forward to help, and solved the problem. Imagine calling such people ‘unskilled’ labourers!

Late in the night we went to look for lions in the forest and succeeded in observing one in the wild. That night, those who were resting in the village heard the roars of the lions with great trepidation! While walking to the Sasan Gir forest, we stopped by to talk to Ismailbhai, a renowned pastoralist and conservator in the area. We asked him when the lions came to that area. He replied, “Lions don’t come and go. They stay here. It is you people who come and go”. We realised immediately the stupidity of our question.

We spent one night in the sanctuary area in Aala vani nes, a village of Maldharis or cattle rearers. Discussions with Vala Bhai about alleged conflicts between livestock and lions generated some interesting posers by him. He said, “we have lived with them, and should be allowed to live with them.” Obviously, many wild life experts may question the ecological and social complimentarity between livestock rearing and lion conservation. But the argument deserves attention.

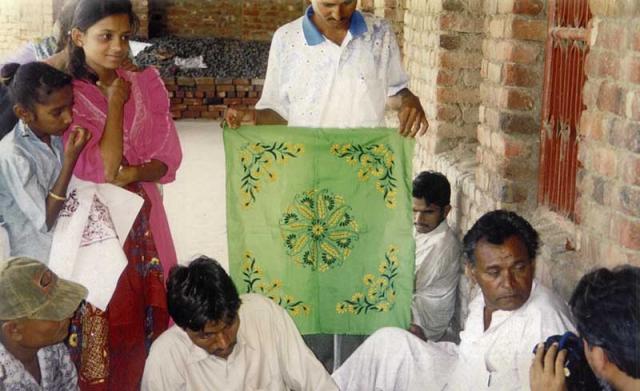

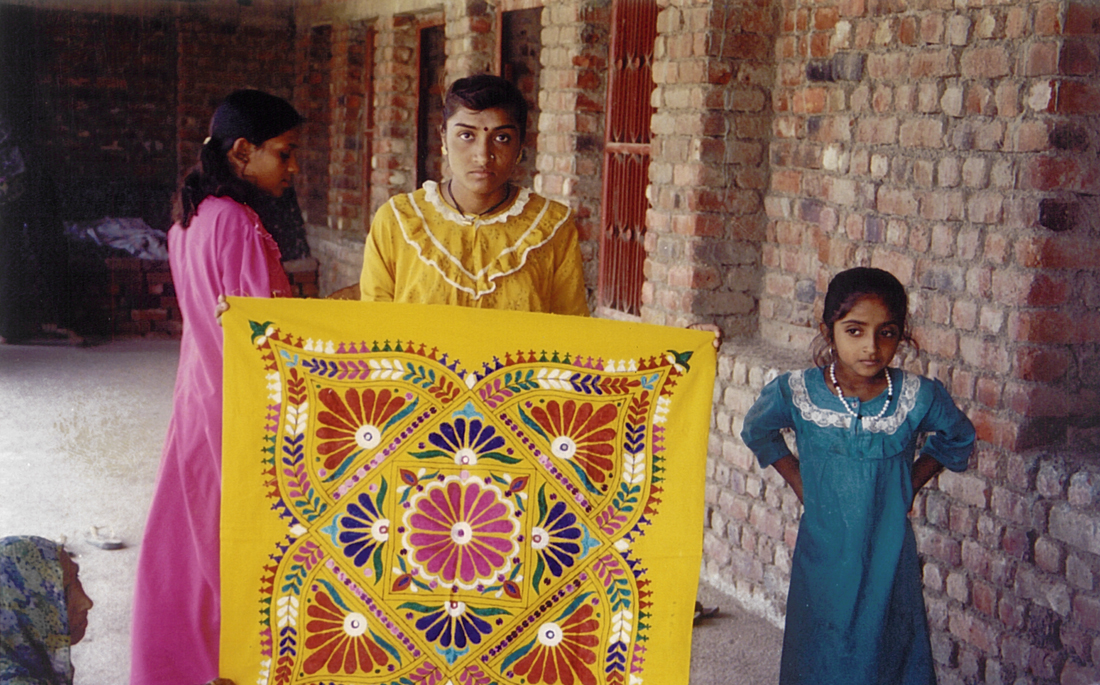

In one of the villages, we organised a small competition and requested elderly women to identify the women who could cook most creatively using uncultivated foods/ vegetables and were the best in embroidery. Biodiversity competitions were organised among children. Prizes and certificates of recognition and honour were given to the outstanding women and children. In general, the participation rate of women was poor and when women did come, they did not sit in the front except in a couple of villages. In Prempura village, we met a 104-year old farmer, Jivraj Bapa, who was still working 14-16 hours every day. He needed neither support for walking nor spectacles for reading. He shared numerous insights with us about sustainable agriculture. He was overwhelmed when we honoured him because none had ever cared to either listen to him or recognise him. We wondered whether it would not be a good idea to invite all such farmer women and men above 100 years of age for a learning workshop about their perceptions and prescriptions for restoring the health of the ecosystems.

We walked through about 50 villages in three districts, Junagadh, Amreli and Bhavnagar. The indigenous as well as externally induced soil and water conservation efforts were most pronounced in Amreli district where water scarcity was also most evident.

Here farmers had tried to use different ways of recharging wells. Some other insights and lessons from the journey:

* In almost every village we stayed, there were one or more farmers who had already made a transition to chemical free agriculture. Policy planners may not see what is happening in the fields, but creative farmers see the signals clearly.

* Many villages have innovators who have never receivedany recognition even within their own village, so much so that they were reluctant to even acknowledge that they had done some thing new. This indicates the depth of prejudice against innovations in our society. * The professionals walking with us were the first to feel tired while some of the field workers, students and farmers were full of energy!

* There was tremendous interest among farmers in the computerised Multimedia as well as the textual data base in Gujarati. It showed how much potential exists for using Information Technology to augment the curiosity of farmers about innovations.

* The gesture of honouring the most knowledgeable people in their own villages moved many people. The idea that creative and innovative people should become points of reference seems potentially very viable.]

The Shodh Yatra was a new experiment for us. We had embarked upon two journeys actually, one outside and visible and the other one within us to discover new meanings of participatory learning. Who amongst us reached where in the inner journey remains to be seen.

FLICKR GALLERY